Photoacoustic spectroscopy is well suited and advantageous method for measurement and analysis of solid and semi-solid samples. It is also suitable for powders, fibers, and samples of very small sizes. The shape of the photoacoustic spectrum is independent of the morphology of the sample, allowing for an ever greater range of different samples to be analyzed using the technology.

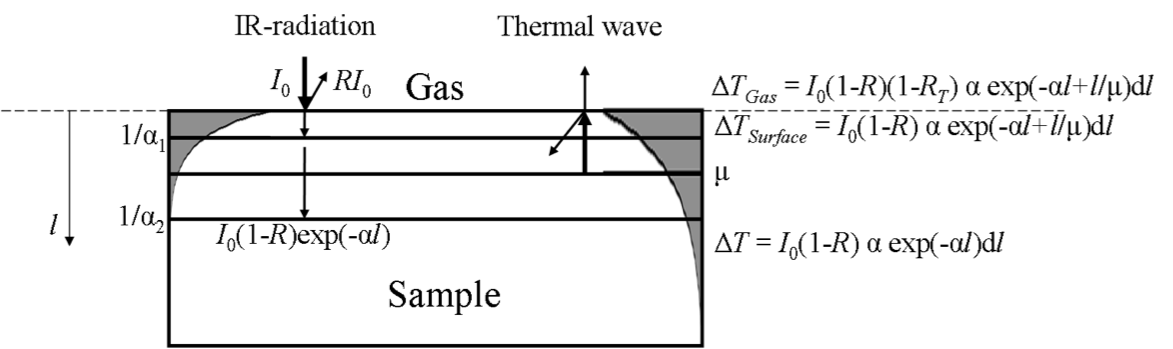

The signal generation process involves absorption of light in the sample and production of heat followed by propagation of heat-generated thermal waves to the sample surface. Heat is then transferred into the adjacent gas leading to changes in pressure. The waves caused by the pressure changes are then measured by a microphone as the photoacoustic signal.

Photoacoustic principle in solid and liquid phase measurements

The sample is sealed inside the photoacoustic measurement chamber and exposed to modulated infrared light through a window. Whether the sample is solid or liquid, the underlying principle of signal generation remains the same. As the infrared light is modulated, it causes the sample to heat up periodically, setting off a chain of thermal and acoustic effects.

The periodic heat flow from the sample to the surrounding gas causes rapid expansion and contraction in a thin layer of gas near the surface—this is known as thermal coupling. At the same time, the changing temperature produces pressure waves that spread through the sample and combine at the surface to create tiny vibrations that interact with the surrounding gas. This phenomenon is called acoustic coupling.

The pressure variations in the gas are then captured by a sensitive pressure sensor aka. microphone, which converts them into a measurable signal. In most solid-phase photoacoustic experiments, thermal coupling dominates the process, while in certain liquids, acoustic coupling can become the prevailing mechanism.

When infrared radiation hits the sample, a portion of it is reflected, with the amount of reflection depending on how much radiation is absorbed by the material. The remaining radiation penetrates the sample according to Beer’s law, with absorption determined by the material’s absorption coefficient at different wavelengths.

If the sample is thin, some of the radiation may pass through and reach another surface. In thicker samples, however, the radiation penetrates deeper into the material instead. The resulting temperature rise in the thin gas layer above the sample surface is influenced by the energy absorbed within the sample—specifically from a depth determined by the sample’s thermal diffusivity.

Solid -phase photoacoustic FTIR

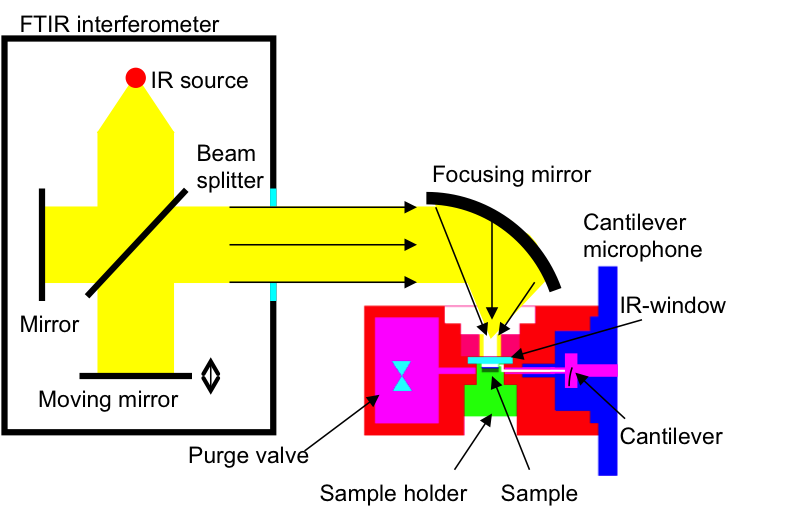

Typical photoacoustic Fourier transform infrared (FTIR-PAS) setup for analysis of solid and liquid samples contains an interferometer, a focusing mirror, and a photoacoustic cell. The FTIR interferometer consists of a beam splitter and two mirrors. The infrared beam is split into two beams: one is reflected from a fixed mirror and one from a moving mirror. By combining the two beams each wavelength of the light is modulated with a different modulation frequency. The combined beam is then focused into the solid or liquid sample in the photoacoustic cell. The generated photoacoustic signal can be directly transformed into an absorption spectrum.

Depth-varying information of the sample can be obtained by varying the mirror velocity or phase angle of detection. Typically for polymer materials the depth from where the spectra is obtained can be varied from few micrometers to about 100 micrometers.

Advantages

The FTIR analysis of solid- and liquid-phase samples has a great variety of applications and advantages compared to other techniques. The most important and best-known advantages are

1. Minimal sample preparation

2. Suitability for opaque materials

3. Possibility for depth profiling

4. Nondestructive measurement, which means that the sample is not consumed.

Applications

Some typical applications of this technology are the nondestructive measurement of

- carbonyl compounds, textiles, and catalysts

- carbons

- coals

- hydrocarbons

- hydrocarbon fuels

- corrosion

- clays and minerals

- wood and paper

- polymer layers

- food products

- biology and biochemistry e.g. proteins, bacteria and fungi

- medical applications such as human tissue

- drug characterization and penetration

- teeth, hair and bacteria